The Mamdani Effect

For years, New York’s political class has made a show of standing with Jews. Now, those politicians are abandoning their past positions almost overnight.

The Mamdani Effect is the collapse of long-claimed alliances with Jews the moment they become inconvenient. It is the legitimization of anti-Israel sentiment at the highest levels of New York politics and the tacit acceptance — even embrace — of the antisemitism that often accompanies that movement.

For years, New York’s political class has made a show of standing with Jews. They have walked in our parades, posed for photos in our synagogues, issued statements after antisemitic attacks, and spoken passionately in defense of Israel’s right to exist. That record was built carefully because it played well politically. But now, with a mayoral race turning toward a candidate who has made numerous antisemitic statements and is strongly tied to organizations that relentlessly single out the Jewish state as the world’s foremost human rights violator, those same politicians are abandoning their past positions almost overnight.

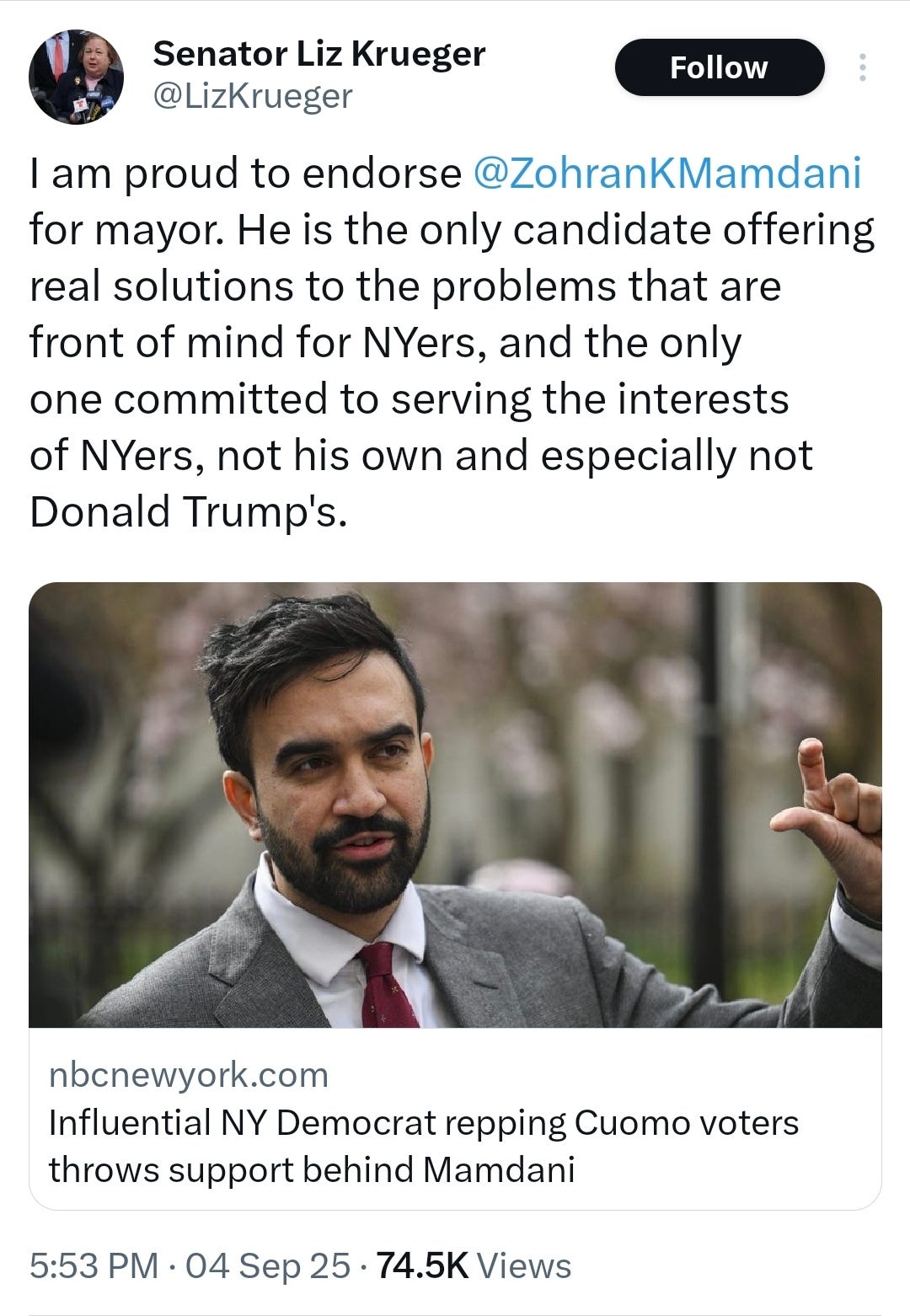

Some have gone further than quiet retreat. A number of city and state officials are openly endorsing Mamdani. These are not people moved by ideology or principle. They are opportunists. They see a candidate who looks like a winner and want their name attached to him early, even if it means endorsing someone who aligns with movements that fundamentally reject Jewish sovereignty. They believe the cost of betraying their Jewish constituents is outweighed by the potential political payoff.

Others are taking a slower path toward the same destination. They are not endorsing him, but they are gradually softening their stance on Israel and shifting toward rhetoric that mirrors the activist left. Andrew Cuomo once signed executive orders aimed at countering the boycott movement. Today he speaks in more careful and qualified terms that dilute his past positions.

These adjustments are calculated political decisions by elected officials who know the record and know the stakes. They understand that Mamdani’s politics leave no room for the Jewish state. They understand that his alliances with certain organizations are not a minor detail but the core of his political identity. And they nevertheless choose popularity over principle.

Jewish leadership in New York has failed in a different but equally serious way. The major organizations that exist to protect the community’s interests seem to have been caught flat-footed. They did not produce or rally behind a candidate with the ability to compete. They failed to create a coordinated plan to keep long-standing political allies from switching sides. They could not convince Cuomo or Adams to sit out the race. Perhaps they assumed Mamdani could not win. If so, that assumption was reckless.

New York City is home to the second largest Jewish population in the world. The idea that such a consequential election could tilt so heavily toward a candidate who is openly aligned with the anti-Israel movement without any sustained, public counter-effort from Jewish leadership is almost unthinkable. It is also proof that our influence is far smaller than critics claim, and that the will to use what influence exists is weaker than we want to believe.

This is about far more than one election. Mamdani’s rise would normalize hostility toward Israel at the very top of city politics. It would give legitimacy to activists who believe that supporting Palestinian rights requires the erasure of Jewish ones. It would embolden anyone in New York who wants to import the slogans and tactics of global anti-Israel campaigns into local politics. And it would send a message to the next generation that such a platform is not only acceptable but potentially a winning strategy.

I think about my grandparents often in this context. They fled Eastern Europe to escape leaders who built their careers on targeting Jews and turning public resentment into political capital. They lived under regimes that claimed moral purpose while destroying Jewish life. They could never have imagined that in New York City, in the twenty-first century, a candidate whose politics carry echoes of the same hostility could be embraced by the political mainstream. What makes it worse is that this is not happening through violence or coercion. It is happening because everyday New Yorkers, many of whom support him out of a misguided sense of virtue, are willing to vote for someone like Mamdani.

The Mamdani Effect is a test, and so far the results are ugly. It shows how quickly politicians will discard their commitments when the political incentives change. It shows how easily antisemitism can be repackaged as a human rights cause. It shows how fragile our alliances really are, and how unprepared many of our own leaders are to confront a challenge of this scale. The mayoral race is a warning. If this is how quickly the support collapses in New York, the place with one of the largest Jewish populations in the world, what happens in places where our numbers are far smaller and our influence even more limited?

If this moment does not shock the Jewish community into rethinking how it organizes and protects itself politically, then we will see this pattern repeat again and again. And each time, the betrayals will come faster, and the consequences more severe.